17M Underage Girls Become Mothers Every Year and They Are So Hard to Reach

By this day next year, about 17 million girls under the age of 19 will have given birth. For many governments and development organizations, these young mothers — most of them in low- and middle-income countries — pose two major challenges:

- Their nutrition needs are often not fully understood or prioritized, and

- They are notoriously hard to reach

“I suspect that in most situations, pregnant and breastfeeding adolescents aren’t getting the nutrition they need,” says the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) Nutrition Deputy Director Dr. Fatiha Terki, who leads the organization’s work in adolescent nutrition.

Adolescence, pregnancy and breastfeeding are all stages of life when a woman or girl has increased nutrition needs. When these periods of time overlap, their nutrient needs compound. This means that the need for nutritious foods is greater for a pregnant teenager than it is for her pregnant adult aunt or her non-pregnant friends.

Sixteen-year-old Hawa Mahamat holds her 7-month-old baby after a check-up as part of WFP’s nutrition program at the Ngarangou health clinic in Chad.

Although adolescents are moving up on the global agenda, adolescent girls remain particularly vulnerable to all forms of malnutrition. The food they eat needs to provide nutrients to fuel both their child’s rapid growth and their own unfinished development. They are at a high risk of anaemia, which during pregnancy increases the risk of low-birth weight babies and maternal mortality. An association between early pregnancy and child stunting has also been widely observed.

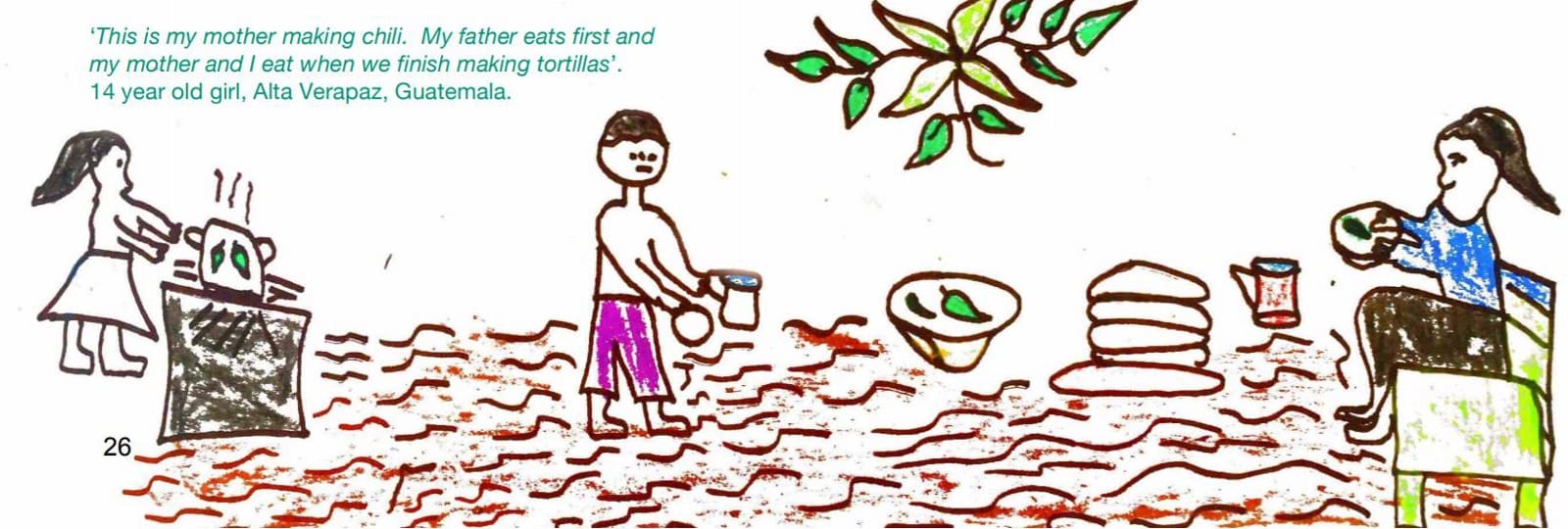

Regardless of high nutrient needs, adolescent girls often eat last and least. U.N. World Food Programme Executive Director David Beasley asks us to visualize a typical family dinner in many parts of the world:

“Imagine a family sitting down for a meal — a father, a mother who’s nursing a little baby, a school-aged boy and an adolescent girl. Who has the most food on their dinner plate? Maybe Dad, since he’s the biggest and has a physically demanding job. Then the boy…then after that, the two slimmest: mom and daughter, right?”

Adolescents use illustration to communicate their feelings around food and identity. Many adolescent girls involved expressed an uneven sharing of food in the household.

While this is how the scene typically plays out, in terms of nutritional needs, the opposite would make more sense. According to the U.N. World Food Programme’s Fill the Nutrient Gap analysis, a pregnant or breastfeeding adolescent girl actually needs the largest share of nutritious foods of anyone else in a household.

And since nutritious foods —especially fresh fruits, vegetables and animal protein— tend to be more expensive than low-nutrient staples like grains and rice, the adolescent mother becomes the most expensive mouth to feed.

Cultural and family dynamics also play a part. Findings from the 2018 Bridging the Gap study carried out in Kenya, Uganda, Guatemala and Cambodia revealed that:

Many unmarried adolescent mothers felt they were a burden on their families and often received only one portion of food to share between themselves and their children.

Aleya, a Rohingya refugee and young mother of four children, is supported by a WFP program targeting extremely vulnerable people in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

The trouble is, when delivering nutrition and health interventions, adolescent girls are notably hard to reach, as the U.N. World Food Programme’s Director of Nutrition Lauren Landis described:

“We know, more or less, that we can find children at schools or new mothers at health clinics. But on any given day, adolescents who’ve left school are scattered across homes, informal workplaces, gardens, farms and so on. Reaching them is another kettle of fish.”

The cultural and UN or government demographic definitions of adolescent can also present challenges, as they are often not consistent. In some contexts, once a girl has a baby, she is considered to be a woman, even if she is still a teenager. Landis has seen plenty of cases where adolescent mothers don’t attend programs designed for youth simply because they no longer see themselves as children.

Bridging the gap

The findings from Bridging the Gap revealed that the needs of adolescents vary wildly across contexts, but there are some common threads. “In all four countries we saw that adolescents wanted services brought to them,” said Lynnda Kiess, a U.N. World Food Programme nutritionist who worked on the study.

“Adolescent mothers need a range of services — from nutrition and health to family planning and prevention of violence and education. But many have busy lives. They don’t want to be pulled into six different directions for six different services. For example, can a pregnancy check-up be combined with nutrition education classes?”

Another common finding was that adolescents wanted to be involved in the design of programs targeting them. “Rather than going ahead and changing the health system, governments, the UN and NGOs should ask the girls how they want to be reached,” said Kiess.

The U.N. World Food Programme is taking steps to better reach adolescents with more tailored programming, says Dr. Terki. “We are committed to supporting adolescents in developing and reaching their full potential,” she said. “We have stepped up our efforts recently to address data gaps internally and to develop an engagement strategy for adolescents that involves several sectors.”

An adolescent mother waits in a community kitchen supported by WFP in La Parada, Colombia, one of the main entry points for people crossing from Venezuela into Colombia.

Yet Kiess stresses that the opportunities to improve nutrition of this vulnerable population go beyond traditional development players. The private sector can play a big role, she says, for example, by fortifying rice with vitamins and minerals, or through using social media and new technologies to influence behavior change.

“We should be thinking of how to serve adolescent mothers in partnership and make sure that nutrition is not being viewed as detached from their other needs.”

Kiess is also quick to point out the bigger picture, that one of the most effective ways of preventing malnutrition associated with teenage motherhood is to delay pregnancies in the first place. “One of the most effective things we can do to prevent early pregnancy is to keep girls in school.”

The U.N. World Food Programme’s support for school feeding programs is a way to do just that, as it motivates parents to send their children to school. Often, they include an additional incentive for girls, such as take-home rations, so parents are more inclined to enroll their daughters.

Dr. Terki reminds us of the exponential power of investing in adolescent girls: “Improving the nutrition of an adolescent girl is a triple whammy: It will improve her life today, while she’s still growing; tomorrow, if she becomes pregnant; and then the life of her child, who will have received the right nutrition at a critical moment. How else do we explain the fact that $1 invested in nutrition gives a $16 return? If this was the stock market, you’d have investors flocking.”

This blog was originally written by Simone Gie and published on WFP’s Insight.

Malnutrition is passed down through generations. Malnourished mothers give birth to malnourished babies, and, every year, more than 3 million children under the age of 5 die from hunger-related causes.