Bolivia

A Country in Progress

With the right to food enshrined its the constitution, Bolivia is committed to ending extreme poverty and hunger by 2025. We’re on the ground helping Bolivia meet this goal, and we need your help.

Help deliver food to Bolivia and other countries.

Bolivia has made great strides in improving food security and reducing extreme poverty – but it’s still one of the poorest countries in South America.

of children under the age of 5 are chronically malnourished

of Bolivians in rural areas cannot afford a basic food basket

of women in Bolivia live in poverty and many face gender-based violence

Bolivia Facts

Population: 12.2 million people

Background: 42% of Bolivia’s population is Indigenous, with 36 Indigenous-recognized nations and 36 official languages. Despite sustained economic growth, there is still significant inequality between urban and rural areas, especially among Indigenous groups and women.

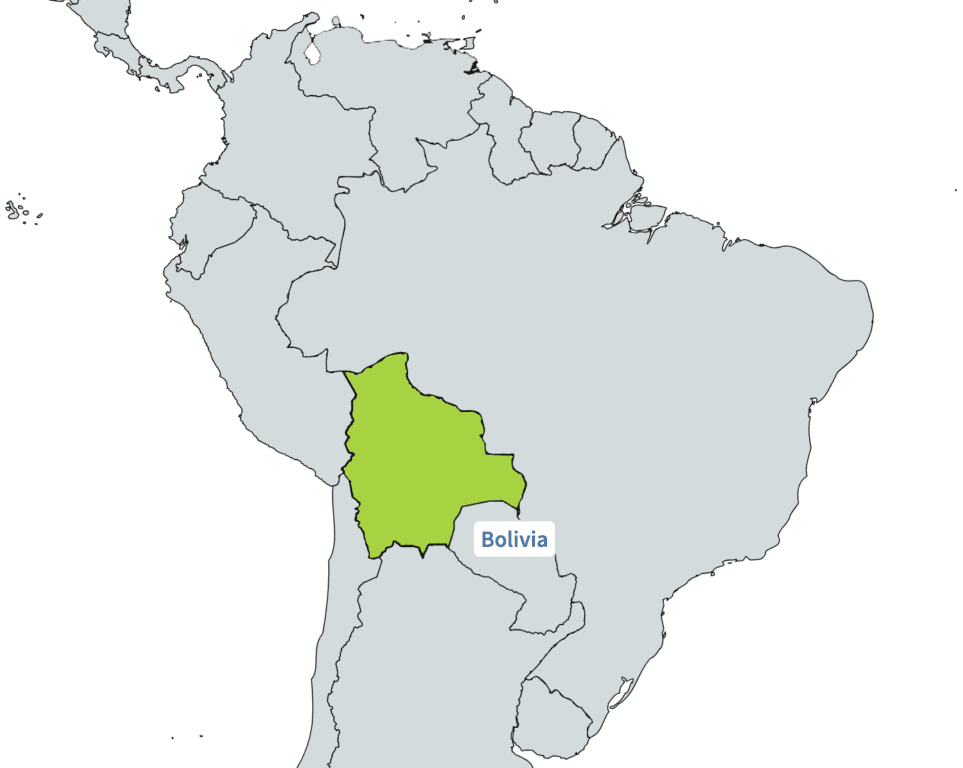

Geography & Climate: Bolivia is landlocked and shares borders with Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Peru. The country has high plateaus, temperate and semitropical valleys, and the tropical lowlands of the Amazon River Basin.

Economy: From petroleum and natural gas to mineral deposits and agricultural products, Bolivia is rich in natural resources. However, economic development is limited by high production costs, poor transportation infrastructure, inequality and the country’s landlocked status. In the last decade, Bolivia has made significant progress on improving food and nutrition security and reducing extreme poverty, but it remains among the poorest countries in South America.

What is Causing Hunger in Bolivia?

Extreme Weather

Bolivia is considered the most vulnerable country in South America to the effects of climate change. In 2016, the government declared a national emergency due to drought, and again in 2018 due to floods. Recurring droughts, floods, frosts and hail hurt the country’s agricultural sector. Analysts predict that people’s vulnerability to hunger will increase by 22% by the 2050 unless serious measures are taken to adapt to a changing climate.

Rural Poverty

More than half of Bolivia’s population lives in rural areas where poverty rates are the highest. Rural communities lack access to vital resources like running water and electricity. 75% of Bolivian families don’t have access to regular access to food. Rural households heavily depend on small-scale farming to survive. They eat only what they can grow themselves and have little to no access to other stable food sources. These families often go hungry during lean seasons, while recurring natural disasters increasingly make farming an unreliable source of income.

Women & Indigenous Communities

Four out of ten women still live in poverty in Bolivia, and gender-based violence indicators are worryingly high. 35% of the country’s Indigenous population still lives in poverty.

Recent History

1993-2003

Resource Privatization & Protests

In 1993, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada became president of Bolivia and began a capitalization program. Through the program, the government’s ownership of electricity, transportation, communications, oil and other industries was sold to private investors.

Protests soon followed and intensified, culminating in 2000 when martial law was declared and several people were killed.

2005-2014

Transition to Nationalization

As the economy entered a recession and violent protests for nationalization grew, Juan Evo Morales Ayma was elected president in 2005. By 2006, he nationalized Bolivia’s gas fields and oil industry. In later years, the government also regained control of electricity and railroads.

Under Morales, a new constitution was enacted that gave Indigenous people more rights, strengthened state control and expanded the president’s terms and power.

2015-2019

Turmoil

In 2015, natural gas prices plummeted internationally, taking a heavy toll on Bolivia’ economy. This was followed by massive wildfires in 2019 that destroyed tracts of forest and grassland in eastern Bolivia.

A controversial election in 2019 caused incumbent president Morales to resign amidst protests.

2020-Present

COVID-19 & Recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Bolivia particularly hard and overwhelmed hospitals. Strict lockdown measures were put in place, which limited employment opportunities and increased poverty.

Elections were delayed due to the pandemic. Luis Arce was eventually elected as the current president.

WFP’s Work in Bolivia

WFP has worked in Bolivia since 1963. Since then, our role has evolved from providing food aid to supporting the government’s efforts to address food insecurity and malnutrition through technical support, advocacy and communications.

We work across Bolivia to raise awareness on nutritional issues and promote healthy diets, especially for women and Indigenous communities.

Small-scale farmers receive cash assistance to meet their food and nutritional needs in exchange for building or rehabilitating infrastructure.

We provide technical assistance to government institutions to increase the efficiency, effectiveness and equity of national programs for food security.

Help Save Lives by Sending Food

When you donate, you help us deliver critical food relief to the most vulnerable people in Bolivia and other countries around the world. You can make difference in someone’s life – send food today.